Running the Everest Marathon…where to start?

Whilst a performance specialist at The Altitude Centre in London, a rush of blood to the head led to my entry into the Everest Marathon and a hefty chunk out of the bank account. Had I ever run a marathon? Nope, not really, maybe close but it’d be fair to say I was far more comfortable on 2 wheels than 2 feet. The marathon is the highest in the world at 5,364m and remains the most arduous challenge I have ever done. I was far from an experienced runner and felt I may have bitten off more than I could chew but everything seemingly came together perfectly for the event in the end. I’m going to attempt to lay out the foundations of how I physically and mentally prepared to complete the race in a little under 7 hours 30 (11th in the international category and youngest competitor in the race).

Moments before the start… lots of nervous energy but stunning views to use as a helpful distraction

First things first, we had to get ourselves to the start line… an 8 day trek from Lukla Airport (nothing more than a strip of tarmac stuck on the side of the mountain, aka. one of the most notorious airports in the world) through the Khumbu* to the base of the mighty Everest. This is an immense challenge in itself and not something I wanted to underestimate in my preparations. The aim of these 8 days is to enjoy the journey, the incredible views, and arrive at Everest base camp (EBC) healthy, energised and injury free. This requires a level of fitness that doesn't need to be specific, you can work on whole body conditioning by simply incorporating a few daily habits to make your body far more resilient… after all you don’t want to waste precious time and energy away from your running schedule. It can be as simple as walking to the supermarket and carrying a bag stuffed with groceries home, cycling to work and taking the stairs when you leave the underground (except at Covent Garden… those stairs are a joke even to a mountaineer!). On top of this some basic core exercises whilst watching Love Island and a robust stretching routine (probably the most important element in remaining injury free and training consistently).

One of the many beautiful days on our hike up to Base Camp, we would be returning back over this path during the race in a couple of days time

Another obvious but under acknowledged element of reaching base camp is acclimatising to the altitude. At 5,364m there is roughly 50% less oxygen available, so therefore less oxygen is taken up by the lungs into the blood. As a result the brain and muscles receive a fraction of the oxygen they are used to, leading to a sense of fatigue and symptoms of altitude sickness (headaches, nausea, etc.), neither of which bode well for running a marathon. Ultimately, to be in any fit state to safely put 1 foot in front of another for 42km, I needed to maximise oxygen delivery to the brain and muscles. The 1st and most important part of this equation is to take your time on the ascent. The body is truly amazing (more than we ever give it credit for) and it reacts to the altitude and makes a sequence of adaptations to ward off symptoms associated with altitude sickness. Our ascent was extremely progressive, 8 days rather than the traditional 5 to allow a more thorough acclimatisation to make running a possibility. The 3 extra days were gained from introducing a rest day each time we crossed 1,000m milestones, where our recommended *rest* included a gentle jog…

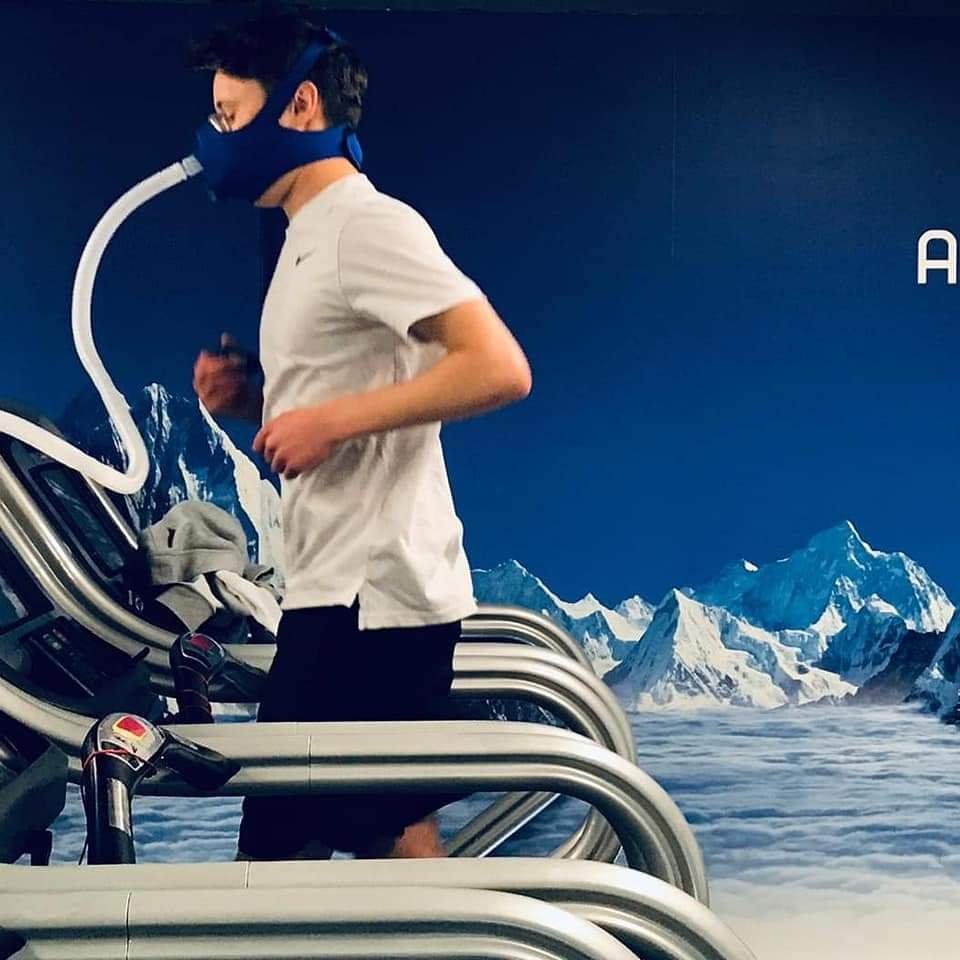

Cranking up the altitude and using a mask to exercise at up to ~5,000m, simulating the race environment. During these sessions the pace was dropped to a plod with a movie on the projector to help pass the time (Marley and Me on this day if I remember correctly)

I was lucky to be working at The Altitude Centre whilst I was preparing so had access to a range of training tools. Even as part of my day-to-day work I would spend a minimum of 4 hours in the altitude chamber at 2,700m - either coaching clients or training myself. As well as this I was pretty regularly sat replying to emails with a mask strapped to my face breathing air equivalent to that of Kilimanjaro (~6,000m), a pretty absurd sight to most but extremely common in our office. Finally, in the month prior to departing, I borrowed an altitude tent which I took home with me and put over my bed. Unfortunately, it didn’t fit in my room so it occupied a corner of the living room to the horror of my housemates (sorry Caitlin and Ems!). By sleeping in one of these specialised tents you are able to constantly remain at altitude resulting in more long-term effects of acclimatising… ie. more red blood cells, YAY!

Hypoxic tent set-up for the weeks leading up to the run

In short, I was able to devise a comprehensive acclimatisation plan in which I spent a lot of ‘training hours’ at my target altitude, as well as normalising exercising in a hypoxic environment. For more details on the techniques and science of using altitude training, keep an eye out for an upcoming post!

Now for the training and what I imagine most people assume included hours and hours, followed by miles and miles of running… WRONG! Well, maybe for the first few months this was the case but I probably ran no more than 10 miles total in the 6 weeks leading up to the event. Not being a runner, I thought I should have at least completed a 42km run before getting on a plane to Nepal, or else the imposter’s syndrome would have been even more real. I chose to enter the Rotterdam marathon, the flattest and lowest marathon in the world, some points even dipping below sea level - excellent prep for one in the Himalayas. Unfortunately, I became more invested in the Rotterdam marathon than necessary and treated it as the race to end all races rather than training for my main goal, the EBC marathon. Motivated to crush my first marathon and spurred on by a silly bet with the stakes of offering 2 days manual labour building a friend's new house extension if I was any slower than 3hr15. Fortunately, I crossed the line in 3hr13 and dodged the manual labour instead sacrificing the integrity of my knee. This knee injury restricted my ability to run, which could have crushed me just 6 weeks before the race but I already had the confidence that the distance would be no issue… I just had to keep the fitness up and get my knee back to a working state. Luckily running off-road, especially at altitude, the pace is certainly not going to be very high, more like a light jog or even a plod at times. I was able to replicate this slow, rhythmic jogging on the bike by matching my cadence (leg speed) with my expected step rate for the race. Whilst better than running for knee injuries, cycling with your feet in a set position isn’t the best and so I topped up the cardio with long, continuous swimming - which allowed my knee to move freely in the water! My physio, Warren, is an absolute legend and 4 days before travelling I was finally able to walk down stars with no pain, but we still had reservations how it would hold up running 42km, let alone on the uneven trails of the khumbu.

Not all of the training was slow plodding, here Liam Hobbins (fellow performance specialist) and I can be seen fighting the nausea during a recovery period whilst completing a training session on the bike at 2,700m

Finally, and in retrospect the decisive factor in a successful race was mental tenacity. In a niche race, such as the Everest Marathon, you are likely to spend a hefty amount of time running alone, questioning everything… “Why am I doing this? How am I going to keep going? Where the f*** is this finish line? Who’s going to know if I just stop?”, and the list goes on. The nature of the event means you will invariably encounter physical, mental and emotional hurdles but the underlining pillar propping up your whole effort is, despite how cliché, your ability to ‘just keep going’. I might be wrong and I’m sure to some extent this can be trained in a specific manner but I’m a firm believer that 99% of this ability comes from experience and overstepping the mark from time to time. From a young age I was involved in endurance sports and have been ‘in the bin’ so to speak on numerous occasions. Often a long way from home and crawling to the nearest corner shop for a bag of jelly babies and a sausage roll. One memory I turn to, when things get really tough, is a bike ride I used to do every year from the age of 12. I’d ride 110 miles to and 110 miles back from my granny’s over the shortest weekend in December, with no phone, just a paper map. Why? I’m not too sure really, I just thought before a hard season of road racing this would be a great way of putting future efforts into perspective… after all, it couldn't get much more lonely than 9 hours lost on snowy roads as a kid, right? The final factor which is essential to arrive at the start line with not just confidence but excitement to put all that hard work to play is to trust the process and your coach (for me, I had to trust myself and the plan I had put together). You have dedicated 6 months to get here, constantly tailoring your plan to maximise potential, accommodate injuries and maintain consistency. The doubts should be addressed and ironed out during training, leaving you with clarity of your capabilities, psyched to get out there and give it your all.

If you’ve made it this far… well done. You must have an interest in suffering (referring to exercise, not reading this article). Hopefully you have a greater understanding of how you can tackle a large and daunting task by employing the ‘cover all bases' strategy before focusing on specific weaknesses as the event approaches. If you have any questions or would like to discuss training for any physical challenge you have in mind please do not hesitate to get in touch and we’ll put a plan together for you. Remember… our body and mind are capable of much more than we can ever imagine!

*a region of northeastern Nepal on the Nepalese side of Mount Everest